Vivian Maier: Self-portrait. Photograph: ©Vivian Maier/Maloof Collection

Tish Murtha: Self-portrait. Photograph: ©Tish Murtha Archive

Note: This reflection focuses on my involvement during the period from the summer of 2015 through 2016 — when the first steps were taken to preserve and reintroduce Tish Murtha’s archive to the wider photographic community.

ACT I — A Fateful Screening

One day in the summer of 2015, I watched a screening of Finding Vivian Maier at Tyneside Cinema.

Afterwards, I wandered over to the Laing Art Gallery to see the Forever Amber exhibition.

Little did I know how fateful that combination of events would prove to be.

Afterwards, I wandered over to the Laing Art Gallery to see the Forever Amber exhibition.

Little did I know how fateful that combination of events would prove to be.

The following day, I visited my mam in Durham. While putting my shoes on to leave, I casually mentioned the exhibition — and that one of the photographs on display was by a photographer who shared her maiden name: Murtha. My mam paused, then told me it was her cousin, Tish, who had sadly passed away two years earlier. I remembered her attending the funeral but had no idea who Tish was, or that she was a photographer.

At the time, a quick Google search brought up just one result — a recent BBC write-up of Forever Amber — featuring one of Tish’s striking images as its main photo. Later that day, something motivated me to sit down and write my very first blog post on my newly created website: a short reflection on Finding Vivian Maier and Forever Amber.

I didn’t yet know that this serendipitous chain of events would be the spark that changed everything.

ACT II — From Bin Bags to Belief

Soon after, my first ever comment appeared on that post — from Ella, Tish’s daughter (and as it turned out, my second cousin). I replied, and on 18 August 2015, I drove from Newcastle to Norton, Stockton-on-Tees, to meet her in person and ask about her mam’s work.

Ella went up to her loft and returned with what could only be described as a battered cardboard box — filled with bin bags and carrier bags — containing her mam’s photographs. As we talked, she told me candidly that while it was her dream for her mam’s work to be seen by the world, she didn’t know where to begin.

In contrast, I’d just seen Finding Vivian Maier, which almost seemed to offer a step-by-step guide for exactly this situation. It felt as if Ella — or maybe Tish — had somehow manifested our crossing paths, and like John Maloof at the start of his documentary journey, I felt a mix of excitement and disbelief at what was spread out before me on the floor.

What Ella had shown me wasn’t just a box of old negatives; to me, it was buried treasure — an unseen archive waiting to be recognised. It also struck me that, just as Vivian Maier’s negatives were discovered in forgotten suitcases, this battered cardboard box felt both tragic and deeply symbolic. Tish’s life’s work was homeless, seemingly discarded by society. It felt incomprehensible.

I took everything home and began to organise it as best I could — a small step towards bringing order to chaos.

18 August 2015: The Tish Murtha Archive as it was. Photo © David Sampele

ACT III - A Journey of Drive and Dedication

The months that followed were like climbing a mountain one careful step at a time, guided by a growing conviction that Tish’s work deserved to be seen. Four moments in particular stand out:

September 2015 — The First Drive South

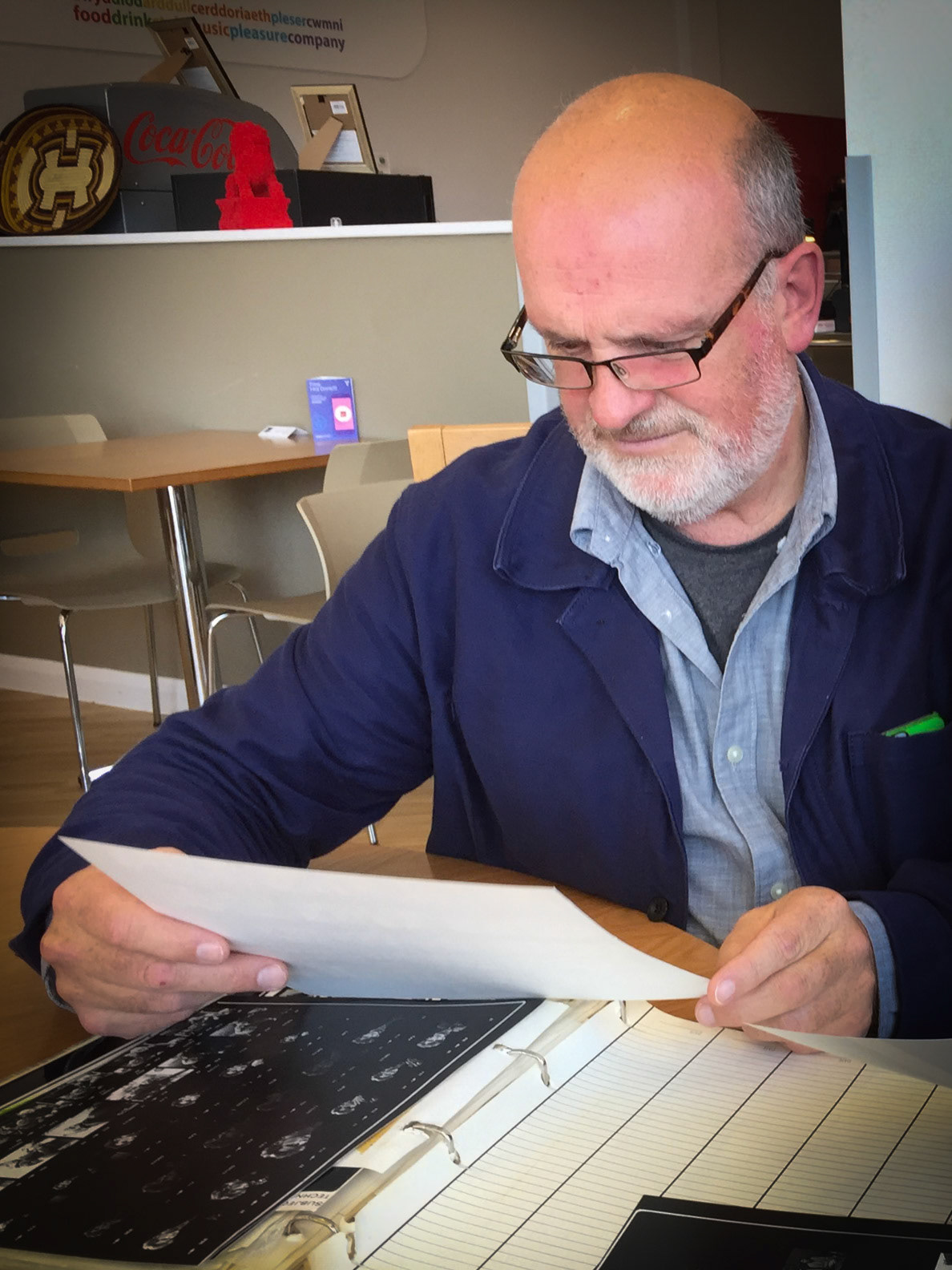

On 28 September 2015, I set off on a six-hour drive to the University of South Wales in Newport, where Tish had once been a student. There I met with photographer and lecturer Paul Reas, who kindly agreed to lead a project on behalf of the university to help organise and begin scanning the archive. After half an hour or so, I jumped back in the car and drove the six hours home — tired, but feeling that the long journey had been worth it.

On 28 September 2015, I set off on a six-hour drive to the University of South Wales in Newport, where Tish had once been a student. There I met with photographer and lecturer Paul Reas, who kindly agreed to lead a project on behalf of the university to help organise and begin scanning the archive. After half an hour or so, I jumped back in the car and drove the six hours home — tired, but feeling that the long journey had been worth it.

October 2015 — Further Encouragement

A few weeks later, while attending a Magnum Professional Practice workshop in London, I mentioned the archive to Dianne Smyth of The British Journal of Photography. I was both surprised and encouraged by her immediate recognition of Tish’s name — and her genuine interest in the story. That brief exchange provided additional motivation to keep going.

A few weeks later, while attending a Magnum Professional Practice workshop in London, I mentioned the archive to Dianne Smyth of The British Journal of Photography. I was both surprised and encouraged by her immediate recognition of Tish’s name — and her genuine interest in the story. That brief exchange provided additional motivation to keep going.

February 2016 — A Digital Presence

By February 2016, I was in Taiwan following the birth of my daughter. Amid sleepless nights, I began building Tish a website and a Wikipedia page — often working quietly while mother and baby slept. Until then, Tish had left behind a fragile legacy known only to a few. She had worked entirely with film, never part of the digital world, so creating an online presence felt like introducing her to a new space that had previously been out of reach.

By February 2016, I was in Taiwan following the birth of my daughter. Amid sleepless nights, I began building Tish a website and a Wikipedia page — often working quietly while mother and baby slept. Until then, Tish had left behind a fragile legacy known only to a few. She had worked entirely with film, never part of the digital world, so creating an online presence felt like introducing her to a new space that had previously been out of reach.

May 2016 — The Return to Wales

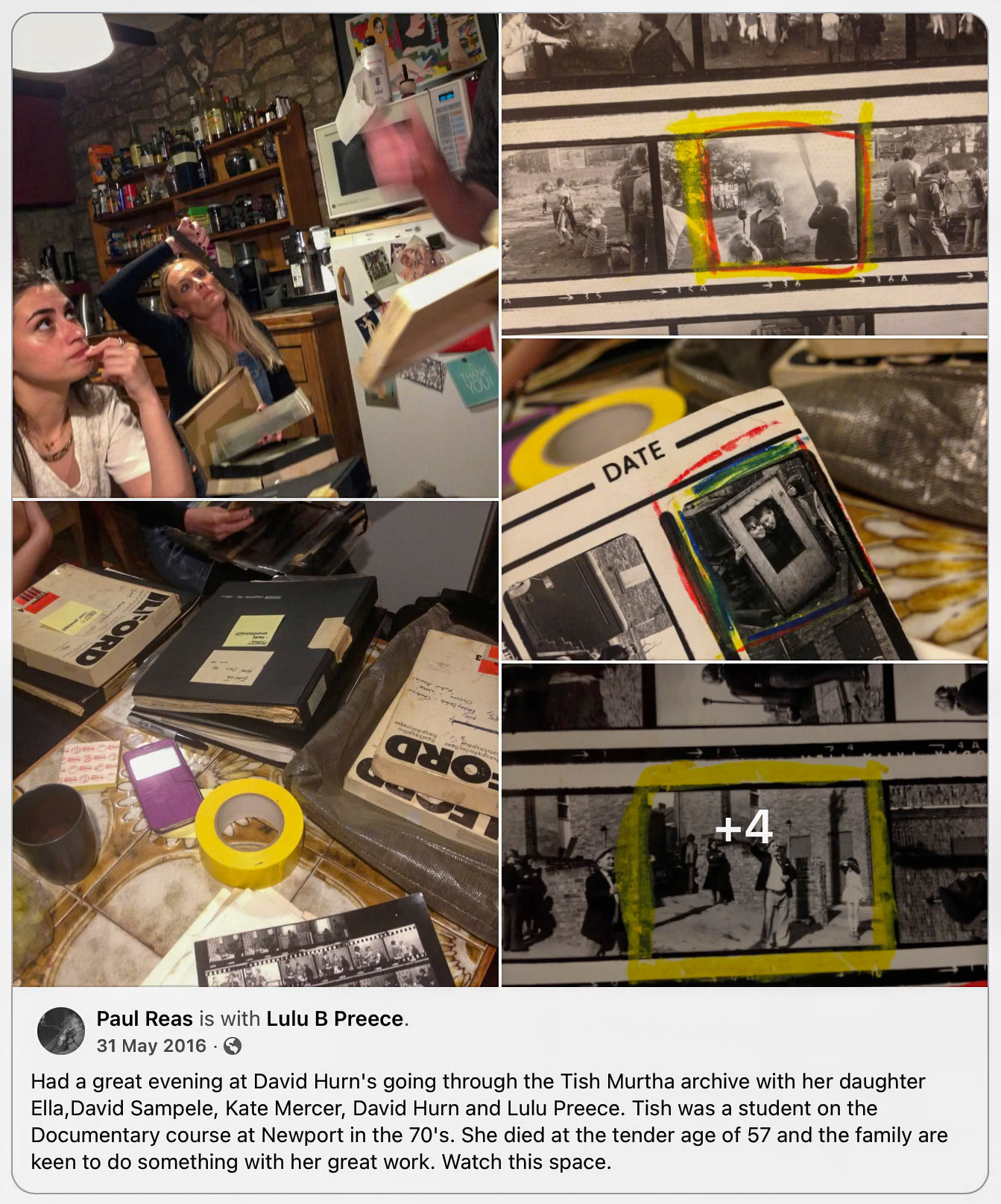

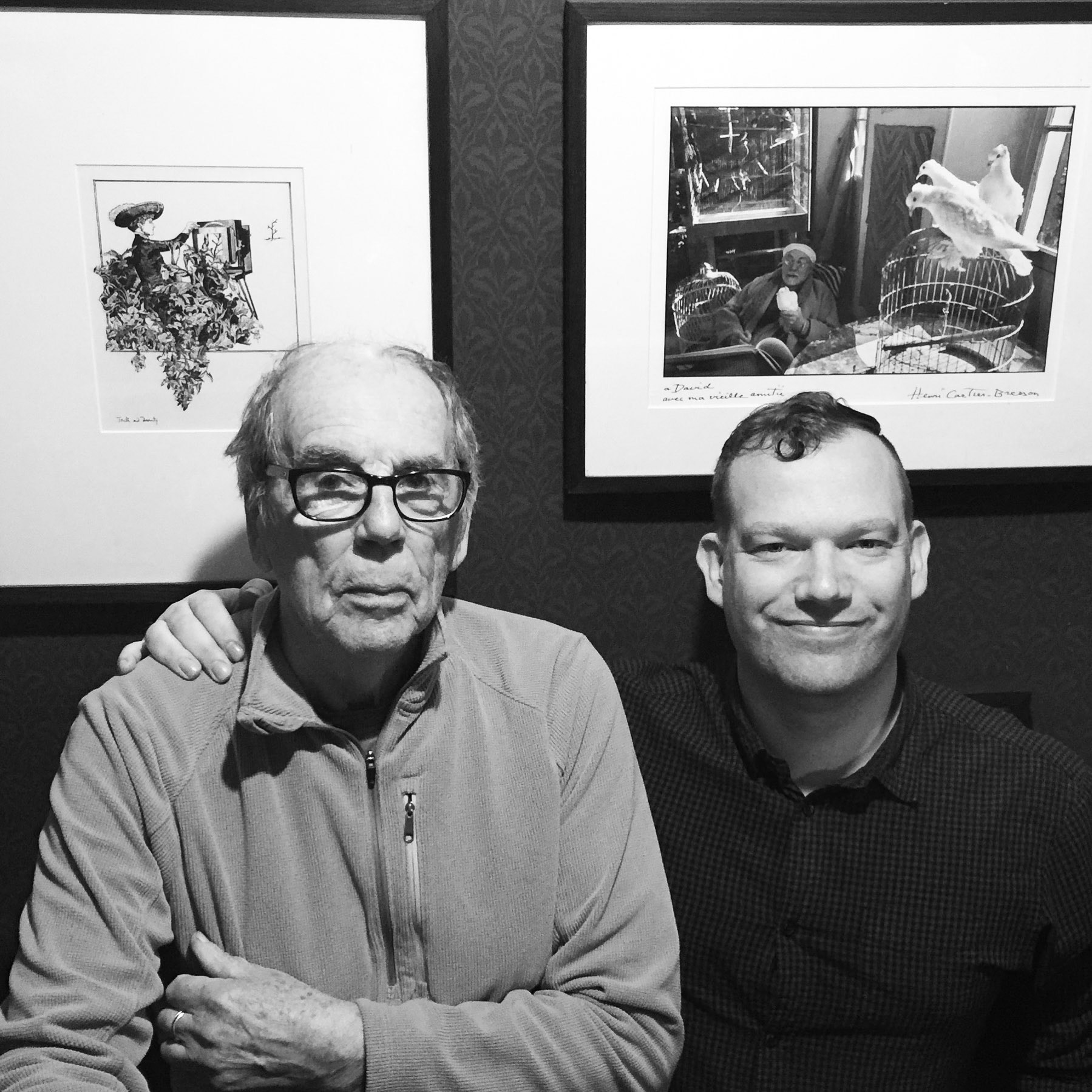

On 31 May 2016, I made the journey again — this time with Ella — driving from the North East to Tintern, Wales, to meet Magnum photographer David Hurn at his cottage and discuss the progression of the project alongside Paul Reas, Lulu Preece, and Kate Mercer. David had been Tish’s lecturer at Newport and remembered her vividly. Both David and Paul’s experience proved as invaluable as you’d expect — their insight, generosity, and respect for Tish’s work helped shape the next steps of what was becoming a much larger story.

On 31 May 2016, I made the journey again — this time with Ella — driving from the North East to Tintern, Wales, to meet Magnum photographer David Hurn at his cottage and discuss the progression of the project alongside Paul Reas, Lulu Preece, and Kate Mercer. David had been Tish’s lecturer at Newport and remembered her vividly. Both David and Paul’s experience proved as invaluable as you’d expect — their insight, generosity, and respect for Tish’s work helped shape the next steps of what was becoming a much larger story.

Those long drives to and from Wales gave me time to think (that and the fact David Hurn's coffee was like rocket fuel, which probably explains why he’s still so active at 91). Each mile added to the sense that something important was taking shape — Tish’s legacy was finally beginning to find its way back into the light.

When Paul Reas later posted “Watch this space” on Facebook, I remember feeling relief — the sense that the archive was finally in safe hands, and that my own part in its story might be coming to an end.

Soon after that meeting I stepped back from the project, while Ella continued the mission to secure Tish's place in British photographic history.

28 September 2015: Paul Reas sees the archive for the first time. Photo © David Sampele

31 May 2016: "Watch this space." Photo © David Sampele

31 May 2016: At David Hurn's cottage Photo © David Sampele

Ten Years On

From a forgotten archive to a lasting legacy

In the years that followed, the rediscovery of Tish’s archive opened the door to the posthumous recognition her work had always deserved. Exhibitions, articles, and a feature documentary reintroduced her photographs to the world — not as forgotten relics, but as vital records of working-class life, seen through a compassionate, unflinching eye.

Tish Murtha: Works 1976–1991 at The Photographers’ Gallery (2018) established her retrospective in central London, bringing her six major series to a national audience. That exhibition was followed by inclusion in major public collections such as the Arts Council, British Council, The AmberSide Collection, and the National Portrait Gallery, and later representation in The 80s: Photographing Britain at Tate Britain — recognition that carried her work from the streets of Elswick to the country’s most prestigious institutions.

And fittingly, like Vivian Maier, Tish now has her own documentary — Tish (2023), about her life and work. Both were coincidentally (?) made available on BBC iPlayer around the same time - a poignant reminder of two photographers’ parallel fates, separated by time and place, yet united by a shared story of rediscovery and recognition.

Summary

Looking back now, years later — having recently rewatched both documentaries with my daughter, who’s since developed her own keen eye for photography — brought everything full circle. A decade earlier, an instinct had led me to discover Tish’s work; and now, sitting beside her, it felt profound to share how photographers like Vivian and Tish had carved their rightful place in a world still too often dominated by men. I always tell my daughter that girls can do anything boys can — and often better. Stories like Tish’s matter because they show what’s possible when someone refuses to let circumstance or gender define their worth.

Trusting that instinct all those years ago changed everything. Bringing order to chaos — arranging Tish’s scattered negatives and prints — became the first step in preserving her legacy. Passing the baton to Paul and Lulu was the next: their generosity and technical dedication transformed those fragile materials into a fully digitised archive that could finally be shared. They understood, as photographers themselves, how delicate creative work can be — and how essential it is to protect it, so others might one day see and feel what the artist once saw. Through their care, work once hidden in the darkness of bin bags now lives in the light — seen, valued, and alive again.